Free Shipping to the Contiguous United States

Screech Owl Breeding Behavior

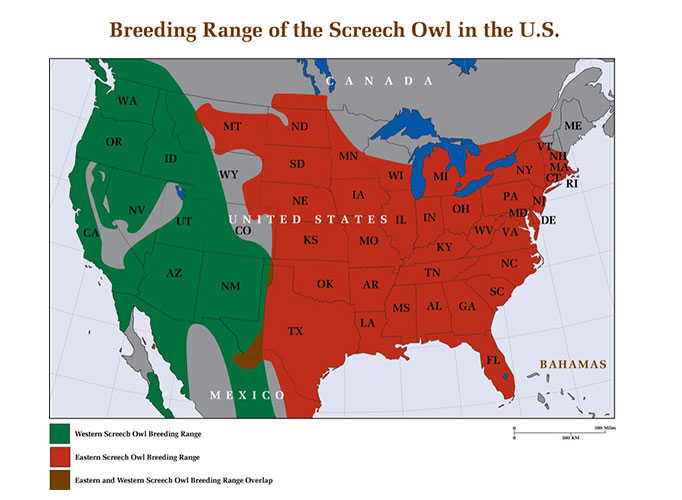

Breeding Habits of the Screech Owl Screech Owl Breeding Season During the snows and winds between late December and mid-February, male screech owls return to the previous year’s breeding sites. These may be holes in trees or nest boxes. Here…